Cardiac Arrest and Chain of Survival

Out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in the UK NHS Ambulance Services attempt resuscitation in approximately 30,000 people each year.

Most cardiac arrests (72%) occur in the home or a workplace (15%). Half of all OHCA are witnessed by a bystander.

The initial rhythm is shockable in approximately 1 in 4 OHCA (22-25%).

A return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved in approximately 30% of attempted resuscitations.

When resuscitation is attempted, just fewer than one in ten (9%) people survive to hospital discharge following OHCA.

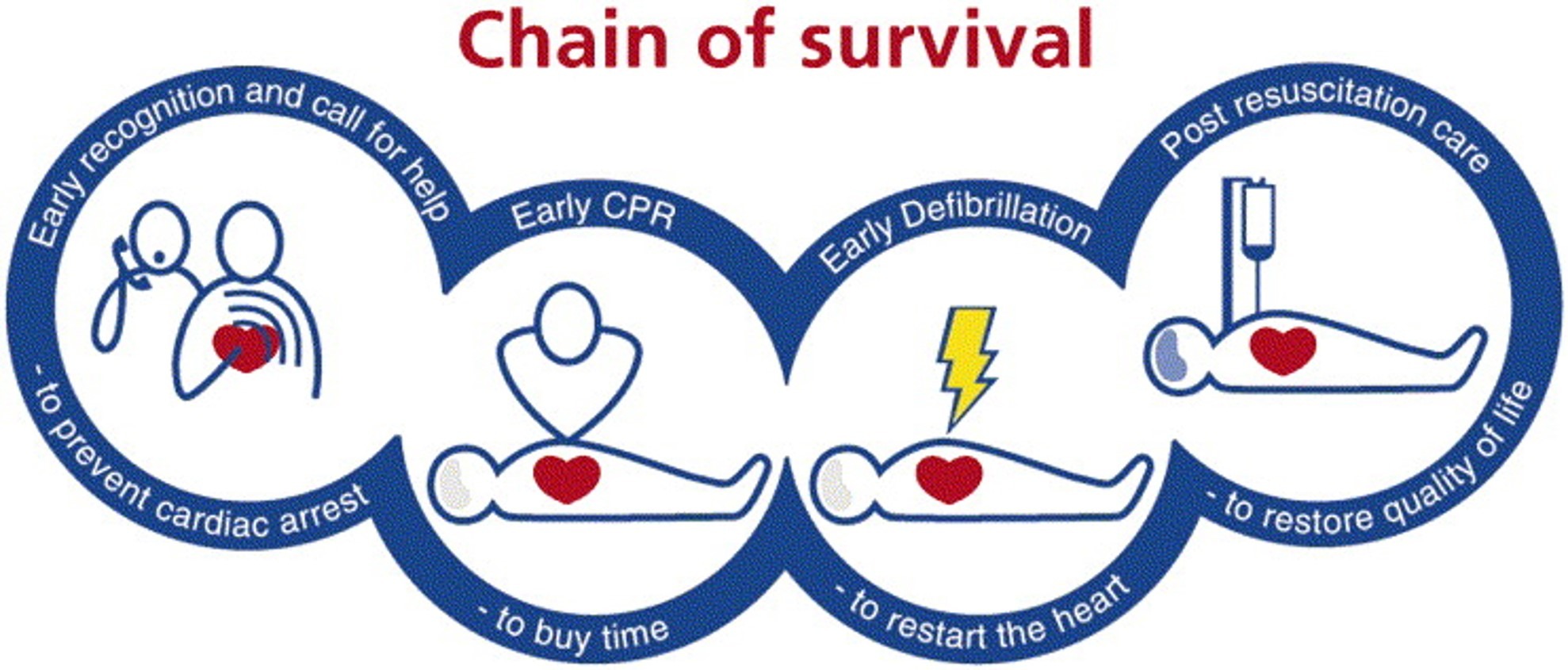

Chain of survival

The Chain of Survival describes a sequence of steps that together maximise the chance of survival following cardiac arrest.

Survival from cardiac arrest depends on a sequence of interventions. The chain of survival concept emphasises that all these time-sensitive interventions must be optimised to maximise the chance of survival—a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

- Prevention & early recognition

- Early CPR – cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Early defibrillation

- Post-resuscitation care

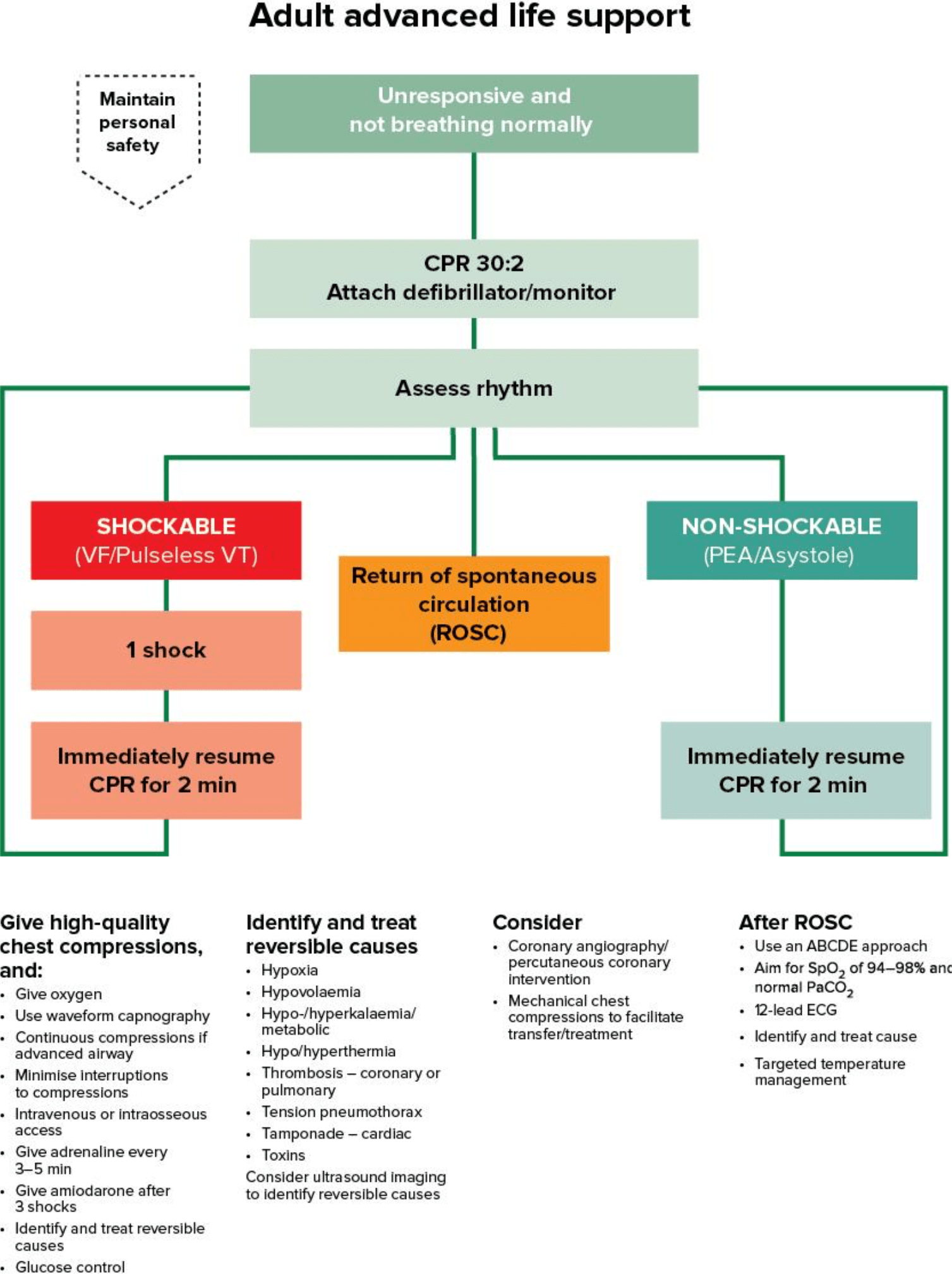

Adult Advanced Life Support

Advanced life support (ALS) may be defined as the use of resuscitation drugs and interventions above and beyond basic life support and AED use. However, if a trained ALS provider attends as a solo responder, they are limited to basic life support (BLS) and defibrillation until other responders arrive.

Advanced life support (ALS) may be defined as the use of resuscitation drugs and interventions above and beyond basic life support and AED use. However, if a trained ALS provider attends as a solo responder, they are limited to basic life support (BLS) and defibrillation until other responders arrive.

The availability of ALS must not affect the provision of high-quality basic life support and appropriate defibrillation.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) management follows similar principles for ALS as in-hospital treatment. It is recognised, however, that the environment, equipment, resources, access to the patient, extrication and transportation of the patient play a pivotal part in the overall clinical management decisions.

A team approach should be adopted as early as possible and a team leader appointed (resources allowing), who can use cardiac arrest checklists for the overall management of the cardiac arrest and for specific clinical skills, e.g. intubation checklists.

Paediatric Advanced Life Support

Paediatric ALS resuscitation broadly follows adult protocols.

Differences between adult and paediatric resuscitation largely reflect a differing aetiology; paediatric cardiac arrest is most commonly due to hypoxia, whereas adult cardiac arrest is usually due to myocardial disease.

The definition of a child is between 1 year and 18 years of age. A clinician should use judgement and information from relatives/bystanders to estimate the age and weight of the child.

Initiate the delivery of good quality BLS on scene, prioritising oxygen delivery, ventilation and chest compressions. ALS procedures including defibrillation if indicated, airway management and establishing IV/IO access to deliver therapies for reversal of hypovolaemia/hypoglycaemia should be considered where resources, training and skillset permit, but should not inappropriately delay transfer to definitive care.

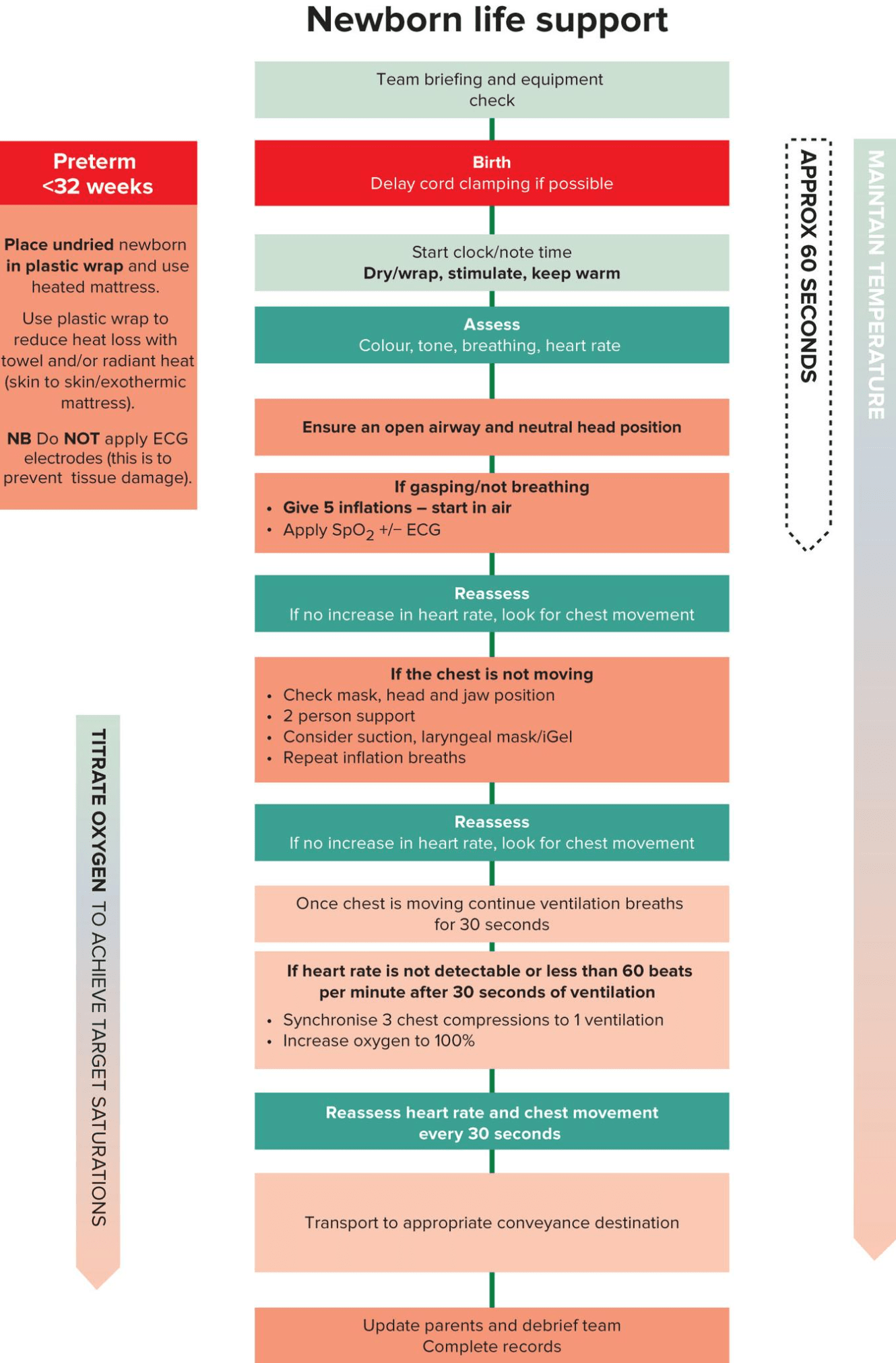

Newborn Life Support

Most, but not all, infants adapt well to extra-uterine life, but some require help with stabilisation, and some require resuscitation. Up to 85% breathe spontaneously without intervention; a further 10% respond after drying, stimulation and airway opening manoeuvres; approximately 5% receive positive pressure ventilation. Intubation rates vary between 0.4% and 2%. Fewer than 0.3% of infants receive chest compressions and only 0.05% receive adrenaline.

The approach to Newborn Life Support guideline outlines this help and comprises the following elements:

- Umbilical cord management

- Thermal care – drying and covering the baby to conserve heat

- Assessing the need for any intervention

- Opening the airway

- Lung aeration

- Ventilation breaths

- Chest compressions.

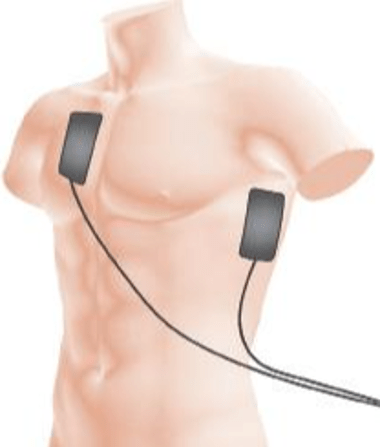

Priorities in Delivery of Defibrillation

Delivering the first shock as soon as possible is the priority.

Therefore, when attending as a solo responder equipped with a defibrillator, immediate assessment of the rhythm and defibrillation (when indicated) should take precedence over airway or breathing interventions. If possible, use a bystander to start and continue chest compressions while the defibrillator is attached.

Although defibrillation is an initial priority, it is important to minimise delays and interruptions in delivering chest compressions.